I am an IBCLC (International Board Certified Lactation Consultant) in private practice in Northern Ireland and a La Leche League Leader with La Leche League of Ireland

What does On Demand (On Cue) Breastfeeding Mean? (and when on demand is not enough)

Women are told a variety of things about how often to feed their baby. Feed on demand, feed on cue, Feed on demand every 3 hours (yep that one's particularly confusing), feed 8-12 times a day. Unfortunately even now some mums are being sent home from hospital with the idea that their breastfed baby should be feeding every 3-4 hours. In this blog I thought I'd delve into what feeding on demand (or on cue) looks like, what are cues for feeding, and what happens if you are feeding on cue but your baby's weight gain is low.

Feeding on Demand / Feeding on Cue

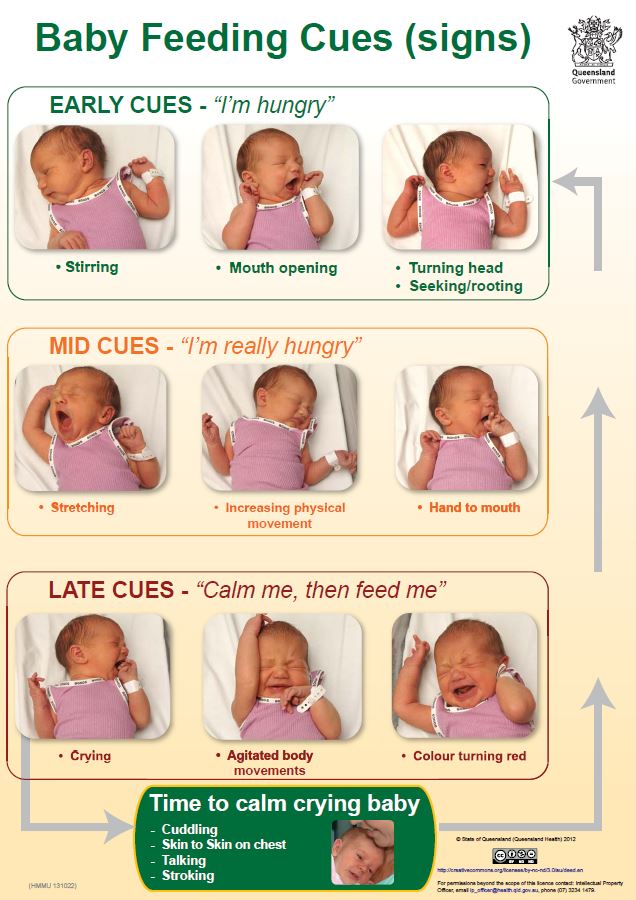

The language around baby led feeding is slowly changing from "On Demand". The word "demand" sounds insistent. To many "demand" gives the impression that a baby cries when hungry and ready to feed. We know, however, that crying is a very late hunger sign. A crying baby is a distressed baby and a distressed baby finds it very difficult to coordinate latching and feeding, so it is actually very hard to feed a crying baby. More recent language focuses on feeding "on cue" or talks about responsive feeding - watching the baby for signs of readiness to feed.

This is a nice poster on the signs of readiness for feeding.

Original image from kemh.health.wa.gov.au/services/breastfeeding/feeding-cues.htm and published here under creative commons licence (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/au/deed.en)

Early cues for feeding are as basic as the baby beginning to rouse from sleep, or opening their mouth while in a light sleep. If a baby is responded to when showing these cues it is usually easier to latch and breastfeed. In this light sleep stage or just awakening, the baby tends to be relaxed and organised and coordinated.

If those cues are missed the baby will become increasingly active to signal the need to breastfeed. If these more active cues are missed the baby will then begin to cry. The very act of crying means that the baby is now stressed, and in more of a sympathetic fight or flight type state. In this state babies tend to be much less coordinated and it is much more difficult for the baby to latch. Not only is the baby less coordinated, but his tongue is in the wrong position. When a newborn cries he lifts his tongue up towards the roof of the mouth. When he latches he needs to bring the tongue down and out to attach under the breast. In practice what may happen with a crying baby is that he puts his mouth to the breast but can't attach to the breast and so continues crying. He may shake his head at the breast or have flailing arms and hands as he can't get latched on well. Perhaps he does manage to latch but the attachment is shallow and the mum has pain and he isn't able to drink easily. All of this causes increased stress for the mum and can make her feel that breastfeeding just isn't working. The baby now needs to be calmed into more of a relaxed state again so that he can latch and breastfeed well. That may take a little time and if this is repeated throughout the day, not only can breastfeeding be stressful, it can also mean that some feeds are missed compared to the number of feeds that would have occurred if breastfeeding happened at the earliest cues. It's not a good situation for either baby or mum.

Skin to Skin and Cues

There's more to consider than just watching for cues though, because whether a baby is being held or lying alone is part of what determines how frequently he cues for feeds. Nils Bergman is a neonatologist whose research focuses on skin to skin contact and how that affects both the baby and the caregiver's physiology. From his research Bergman shows that babies behave differently if held, compared to if they are lying without contact with a caregiver's body. When held on a body a baby enters a specific program of feeding and brain building. In this quote SSC stands for Skin to Skin Contact.

After feeding the baby goes to sleep, and research has shown that only on mother’s body is this sleep of the right quality for brain wiring. Sleep cycling is necessary for brain development, and SSC achieves REM sleep cycling with Quiet Sleep. When the baby wakes on mother, there is time for smell to initiate a cephalic phase preparing the stomach for food, so that when the baby starts to feed it is primed and prepared, and organized in its feeding.

http://www.skintoskincontact.com/ssc-breastfeeding.aspx

Bergman explains that sleep cycles last approx 1hr-1.5 hrs. When held on mother's body a baby completes a sleep cycle and then wakes to feed. So when being held, a baby will cue to feed every 1-1.5 hrs. Since it's normal for primate mammals to be in contact with their babies, this is a normal feeding frequency for our babies. In contrast, if a baby is not in contact with mum's body, (e.g. in a moses basket, even if it is right next to mum) the normal state of feeding and sleeping doesn't happen. The baby doesn't enter the same sleep cycling program. So a baby who isn't being held may not cue for feeds with the same frequency as one who is being held. I should just reiterate that the frequency for the babies who are held is the normal frequency.

Babies who are not cueing for feeds at normal frequencies (maybe only feeding 3hrly), or not being responded to at early feeding cues may have more difficulty with breastfeeding and may have more weight gain issues.

When Feeding On Cue might not be enough

Healthy babies who are feeding well and gaining weight appropriately cue for feeds when they need them and are able to manage their own intake. We have known this for 25 years and this is why mums are encouraged to responsively feed when their child cues readiness. A baby who is unwell, or a baby who isn't gaining weight appropriately however is another matter, and it is the latter that I want to talk about most. Many babies in our medicalised system of birth don't get off to the best start to breastfeeding. We have a large percentage of inductions, instrumental births (forceps / vacuum) or cesareans. Many babies are sleepy after birth , perhaps due to drugs during labour. Many babies have some separation from mum (even if it is short). These deviations from normal physiology mean that lots of babies don't feed well in the early days. This has a knock on effect to mum's milk supply as these babies just don't stimulate milk production as well as they should. This can result in a baby who has low weight gain in the first week or 2. See this previous blog on what weight gain should be and what to do to improve it. In many of these cases the mum is following the baby's cues, but the weight gain continues to be low. So what is going on? Well, in essence I think that in the early days breastfeeding and milk supply drops into one of 2 cycles.

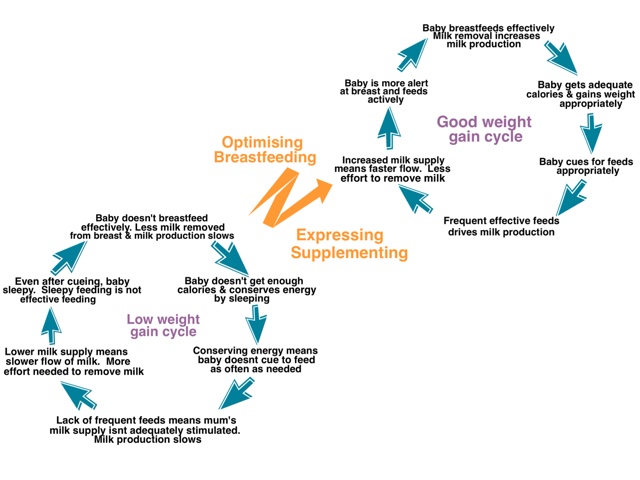

These are vicious cycles which feedback on themselves, centring around how much milk a baby drinks from the breast and how well mum's milk production builds up. If a mum has a good milk supply and lots of milk in the breast, then milk flows easily. Mum's body easily delivers the milk to the baby. If supply is low, then it is harder work to remove the milk. The milk supply of course is driven by how well a baby feeds so milk production and how well a baby feeds are closely linked.

If a baby is not feeding well in the early days, mum's milk supply doesn't build as it needs to. A baby may then fall in to a declining spiral where he sleeps more, doesn't cue for feeds and when he does feed, he doesn't get as much milk (due to the joint issue of sleepy feeding and low supply requiring more effort to feed). In contrast, if feeding goes well in the early days then the dyad move into an upward spiral where baby gains weight well, cues for feeds frequently, milk flows easily and baby feeds well.

If this weight gain issue is identified in the early weeks then some simple interventions can move a baby from the declining cycle into the upward cycle. Interventions should always involve optimising breastfeeding (looking at frequency of feeds, how a baby is positioned and attached, maximising the amount of milk that a baby drinks when at the breast, and resolving any physical issues that was preventing good milk transfer). Interventions might also involve expressing and supplementing mum's milk alongside breastfeeds. That expressing increases mum's supply (so milk will flow more easily). Supplementing that milk gives the baby more calories with less work required so that baby starts to gain weight better. Depending on age of the baby and what the weight gain is like, there may also be a requirement for some temporary supplementation of either donor milk or formula. Often a very small amount of supplementation helps a baby to feed better at the breast. Feeds actually become more effective as the baby has more energy, is more alert, feeds more actively without falling asleep, and therefore removes more milk. Crucially these interventions may also involve not waiting for the baby to cue for feeds. It means recognising that a baby not gaining appropriate weight may not be able to correctly cue for feeds and that feeds should be offered to the baby frequently.

Any supplementation to increase gain should be introduced with a plan so that both the family and the HCP know why supplementation is being given, what the goal is, when it will be appropriate to wean off the supplementation and how that weaning off will happen. It should not be a case of an HCP casually mentioning the need to add in top-ups with no end in mind (see this blog on the top-up culture). Don't be afraid to talk to your HCP about your goals. If your goal is to exclusively breastfeed your baby, see this intervention as temporary, as a way to allow you to get to exclusively breastfeeding with healthy weight gain. A tool which will allow you to breastfeed for as long as you wish. Create a plan together which will allow you to meet that goal. As ever, if you don't feel that you are getting the support you need to meet your goal, or in creating a plan to normalise your baby's weight gain then look elsewhere. Contact a local breastfeeding counsellor or IBCLC (Lactation Consultant) for help.

Babies gaining appropriately (approx 1oz / 30g a day in first 3 months) cue for feeds and manage their milk intake appropriately. Babies who aren't gaining appropriately .... not so much. They are simply a bit compromised. Their bodies compensate for the lack of weight gain by conserving energy. They sleep more, they feed less well, and to top things off, our Western culture contributes by encouraging separation from our babies. Having our baby right beside us in a cot / Moses basket / pram etc may not seem like separation for us, but it is a huge thing for our babies. Our babies need body contact and they need frequent feeding. In contrast our mums are often not aware of just how often babies feed, and unfortunately our culture bombards us with these unrealistic 3-4 hrly timescales.

Earlier today I watched a documentary on TV about bears. It followed one first time mother bear and her cub. It struck me how carefully it explained that the cub was completely dependent on mum and needed to feed every few minutes. I think that when we are able to embrace this normal mammal model for ourselves, rather than separating our mums and babies and giving unrealistic ideas of feeding frequency) breastfeeding will be easier for many mums and babies.

If you have any questions about a consultation or would like to arrange to meet, please get in touch.

Important Information

All material on this website is provided for educational purposes only. Online information cannot replace an in-person consultation with a qualified, independent International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) or your health care provider. If you are concerned about your health, or that of your child, consult with your health care provider regarding the advisability of any opinions or recommendations with respect to your individual situation.