I am an IBCLC (International Board Certified Lactation Consultant) in private practice in Northern Ireland and a La Leche League Leader with La Leche League of Ireland

Breastfeeding, Fertility and Subfertility - How Breastfeeding affects your menstrual cycle

Breastfeeding is part of the reproductive cycle. This cycle begins at the start of a menstrual period, progresses through ovulation, conception of a baby, pregnancy, and birth. Lactation completes the cycle whether or not you choose to breastfeed. All women will begin to produce milk in pregnancy and will produce milk after birth.

For most women who breastfeed, her fertility is suppressed for some time after birth, as her body continues to devote energy to grow her new nursling. In this way lactation is a continuation of the work of pregnancy. At some later stage the women's fertility will return and she will become capable of getting pregnant again and starting a new reproductive cycle. When her fertility returns varies widely and is hugely individual. Where one breastfeeding women may get her period back at 3 months pp while fully breastfeeding, another women may find herself frustrated as she is now 18 months post-partum, desperately wants to have another baby, but hasn't had a period yet.

I have split this blog on fertility into 3 parts, otherwise it would be impossibly long. The first part will explore how breastfeeding affects fertility generally and how it impacts the return of fertility. Part 2 will look at how you can use this information either as birth control or to maximise your chances of conception while breastfeeding. Part 3 will look at breastfeeding in pregnancy and whether there are risks to the pregnancy from breastfeeding.

The Menstrual Cycle

Before we can understand how breastfeeding affects the menstrual cycle, we need to understand how the menstrual cycle works. There is a very complex interaction of hormones so I'm going to give just the most basic of overviews that allows me to concentrate on the breastfeeding aspect. I'm also going to break the cycle down into individual steps so that I can then explain how breastfeeding affects each step. Even though I've tried to not get into too complex an interplay it's still reasonably complex so stick with me. Here goes...

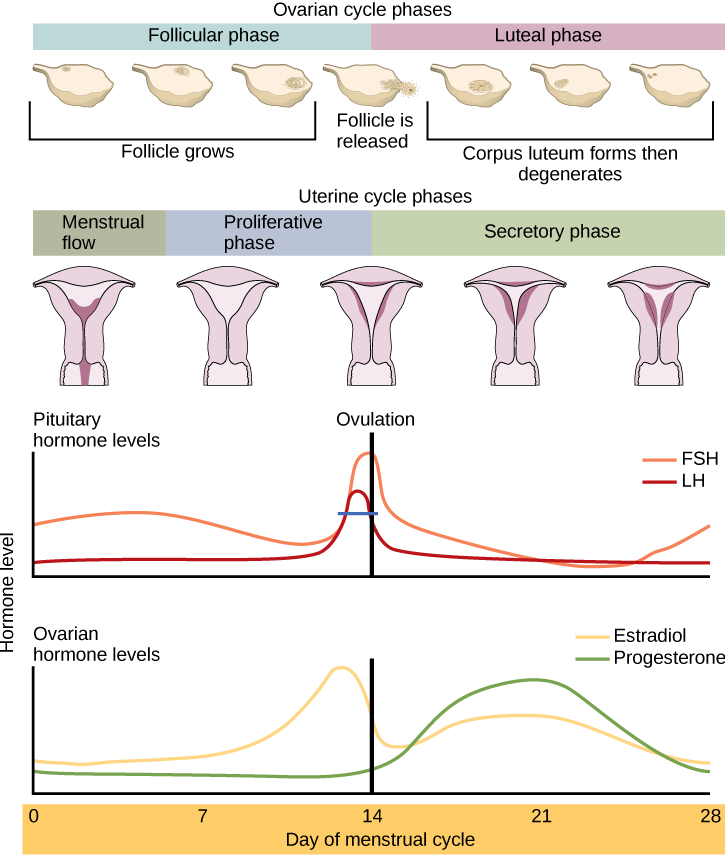

Day 1 of the menstrual cycle begins on the first day of bleeding and begins what is known as the follicular phase. The follicular phase begins with the start of the menstrual flow of blood, and ends with ovulation.

The follicular phase is focused on the development of egg follicles, and the preparation of an egg for release at ovulation. This happens through a series of hormones and feedback loops from those hormones. The main hormones at play here are:

GnRH - Gonadotrophin Releasing Hormone

FSH - Follicle Stimulating Hormone

LH - Luteinising Hormone

Oestradiol (a form of oestrogen)

Progresterone

GnRH may be the one hormone listed here that you haven't heard of before. Think of GnRH as the master switch. It essentially acts as a messenger telling the pituitary to release the other hormones. Oestradiol can have different spellings depending on whether you are reading a UK based article (oestradiol) or a US based on (estradiol). I will be using the UK spelling.

So lets look at the basic mechanism of egg production.

Step 1: The process begins with GnRH causing the pituitary to release FSH/LH and begin developing the follicles.

Step 2: The developing egg follicles in turn produce oestradiol and progesterone, but the levels are relatively low. Low levels of Oestradiol suppress GnRH. High levels of Oestrodiol stimulate GnRH. This feedback means that low levels of FSH and LH continue to be released allowing the eggs to develop further. 1 egg is then selcted for maturation. As it matures it produces more oestradiol and this further suppresses GnRH & FSH (see the decrease in the orange line around day 7). This drop in FSH causes the rest of the follicles that were developing to degrade leaving the 1 selected follicle to develop to full maturity. (Occasionally it is more than 1 egg - but I want to keep this from getting complicated).

Step 3: Oestradiol release now increases rapidly from the selected egg rising to a peak level (yellow line in diagram). Low levels of Oestradiol suppress GnRH. High levels of Oestrodiol stimulate GnRH. Now that the oestradiol has peaked and reached a high level, it causes a massive spike in GnRH (releasing high levels of FSH and LH). This is what triggers the release of the egg (ovulation). The important thing to note here is that oestradiol has to peak in order to trigger enough GnRH (and corresponding FSH and LH ) to release an egg. So an egg has to reach a certain level of maturity in order for ovulation to occur.

Step 4 - After ovulation begins the luteal phase of the cycle. The luteal phase begins with ovulation and ends with the start of the new bleed in the next cycle. When ovulation occurs the egg makes it's way to the fallopian tube. The left over follicle from which the egg was released now becomes a structure called the corpus luteum, which continues to produce hormones. It produces pretty low levels of oestradiol and much higher levels of progesterone. This low oestradiol level suppressese FSH and LH, so that no further eggs develop and causes the uterus lining to further develop.

What happens next all depends on whether the egg meets a sperm or not and how this impacts the corpus luteum.

On average the corpus luteum "lives" (is productive) for 12 days. If the egg is not fertilised, the corpus luteum pumps out those hormones for several days and then it starts to degrade. As it degrades it stops producing hormones and so the oestradiol and progesterone levels drop rapidly (see the green and yellow lines in the diagram towards the end). The particularly rapid drop in progesterone then triggers the shedding of the uterine lining and the next menstrual cycle begins. The drop in oestradiol and progesterone allows FSH to begin to rise to start developing new egg follicles for the next cycle.

If the egg was fertilised however the corpus luteum does not degrade after 12 days. Instead the newly fertilised growing cells signal the corpus luteum to continue to produce high levels of progesterone and to maintain the uterus lining for implantation and growth. This progesterone production is vital to maintain the pregnancy, and is required until the placenta fully takes over the hormonal maintenance of the pregnancy at around 14 weeks. A healthy corpus luteum is vital for sustaining a pregnancy and this is something I'll discuss in more detail in Part 3 on whether breastfeeding could potentially impact pregnancy and risk of miscarriage.

Breastfeeding & The Menstrual Cycle

So now that we have an overview of the menstrual cycle lets look at how breastfeeding impacts it, and why breastfeeding suppresses fertility. In an 2002 article called Lactational Control of Reproduction, McNeilly states,

In women, suckling increases the sensitivity of the hypothalamus to the negative feedback effect of oestradiol on suppressing the GnRH/LH

Each time we breastfeed the suckling has an effect on this GnRH pathway. The more that a baby suckles, the more of a effect is produced. It is not yet fully understood exactly how suckling causes the change but writing in another 1993 journal article called Lactational Amenorrhea, McNeilly says:

Suckling appears to suppress the normal pattern of pulsatile release of GnRH and hence LH and prevents the normal growth of follicles.

The normal positive feedback effect of estrogen on LH release is abolished, and estradiol exerts an enhanced negative feedback effect on both LH and FSH.

Thus, while suckling continues, any follicle that starts to develop and secrete estradiol will inhibit further LH release and therefore stop growing.

When suckling declines, the pulsatile pattern of LH returns to normal,

sensitivity to estrogen negative feedback declines, and follicle growth can continue and ovulation will occur.

...

Thus, while the suppression of fertility in breast-feeding women plays an extremely important role in limiting populations, the mechanism whereby the suckling stimulus from the nipple causes the disruption in GnRH release from the hypothalamus remains to be elucidated.

So essentially a lot of suckling prevents the complete development of an egg, by preventing the normal secretion of FSH and LH.

Return of Fertility

The return of fertility is generally through a phased process. Immediately post-partum babies generally spend long periods of time at the breast suckling (this obviously assumes no separation of mum and baby). Assuming all is well, babies spend most of their time suckling in the early weeks (including while asleep). During this stage Step 1 of the menstrual cycle does not occur. Eggs do not develop due to the suppression of GnRH from the intensive suckling.

As babies get older they typically spend less time at the breast. Babies get more efficient at the breast, they become more physiologically stable (whereas newborns rely on sucking to regulate behaviours like breathing and heart rate), and they become more interested in toys and life around them. As they become more established on solids, suckling typically reduces further.

As the suckling reduces below a certain level (perhaps an individual level for each women) the suppression of GnRH is reduced and follicles begin to develop. Step 1 completes. As the follicles begin to develop they produce some oestrogen. Low levels of Oestradiol suppress GnRH. High levels of Oestrodiol stimulate GnRH. McNeilly also tells us that breastfeeding exacerbates the suppression. This means that although follicles begin to develop, they do not complete development. Step 2 does not occur.

As suckling reduces further, follicles develop to a more mature stage but the suppression is still enough that the LH surge does not occur and so ovulation does not happen. The egg is not released. Step 1 and 2 complete, but step 3 doesn't.

The next stage in fertility resuming happens when the egg matures enough to release a peak of oestradiol, causing FSH and LH to peak and to allow ovulation to occur. However although ovulation occurs the corpus luteum may be considered inadequate. What essentially happens here is that an egg develops and is released, but due to the suckling the egg isn't fully mature (oestradiol never got quite as high as it would have without any suckling). As the egg isn't fully mature, the corpus luteum isn't fully mature. If you look back to Step 4 - the corpus luteum should produce high levels of progesterone for around 12 days and then degrade. The drop in progesterone due to that degradation then triggers the period a couple of days later. This is why you typically get 14 days between ovulation and the next period. If the corpus luteum is inadequate however it doesn't produce progesterone for the length of time that it should. It is sub-mature and degrades earlier. This means that you get less days between ovulation and the next period. Perhaps only 10-12 days for example. This can be a problem if you are trying to get pregnant.

Lets say that ovulation happens on day 14 (for many women it is earlier or later than this). The egg then makes it's way to the fallopian tube, where it may become fertilised a couple of days later. It then needs to make it's way to the uterus to implant and grow. It takes another 5-7 days to get to the uterus, and then needs a lining which is thick and ready for implantation to happen. The process of implantation may take 2-3 days. Once that has happened a feedback mechanism should be in place which keeps the corpus luteum alive and functioning and producing progesterone in order to stop the uterus lining from shedding. So it could take 10 days after ovulation till an egg is fully implanted in the uterus. If the corpus luteum is immature and progesterone levels have started to drop early it becomes less likely that a fertilised egg isn't going to make it to the stage where it is fully implanted in the uterus before the lining of the uterus responds to the dropping hormones and starts to shed. It can difficult to get pregnant if the luteal phase is less than 12 days (known as a luteal phase defect). A woman may be having regular periods at this point but she is actually still sub-fertile. Step 1, 2 and 3 are completing but step 4 isn't completing sufficiently to sustain a pregnancy.

Finally when suckling has reduced sufficiently all the steps complete and the woman becomes fertile. McNeilly describes all of this in a 2001 article in the Progress in Brain Research Journal:

Breast-feeding through the suckling stimulus suppresses fertility for a variable time after birth. Initially there is a period of pituitary gonadotroph recovery from the suppressive effects of the high steroid levels of pregnancy, followed by a period of suppressed ovarian activity associated with limited follicle growth. During this period of breast-feeding-induced amenorrhea, the pulsatile secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH), which reflects hypothalamic gonadotropin-releasing hormone (GnRH) release, is erratic and much slower than the one pulse per hour required in the normal follicular phase of the menstrual cycle to drive follicle growth. At some time the suckling stimulus drops below a threshold resulting in a resumption of reasonably organized pulsatile LH secretion, which is associated with development of follicles and some steroid secretion. However, positive feedback of estradiol which triggers the preovulatory LH surge and ovulation appears to be blocked by continued suckling, until suckling is reduced further and positive feedback and ovulation resumes. Often while women continue to breast-feed the first few ovulations and menses are associated with inadequate corpus luteum function, which would probably not support a pregnancy. Eventually normal menstrual cycles resume when suckling declines further.

Time for Return of Fertility

The time it takes for any woman to pass through these phases of returning fertility is hugely individual even if they breastfed in exactly the same way and for the same lengths of time. A study by Lewis et al in 1991 looking at 89 women in Australia who breastfed for longer than average found that the women had an average of 322 days without ovulating and 289 without a period. So on average the women had a period after 9 months post partum, although didn't ovulate until a later cycle. The longest time without ovulation in the study was 750 days - over 2 years.

In NI where combined breastfeeding is common and where women are culturally encouraged to quickly get their baby on to "3 meals a day" it is common for many women to find that their period returns soon after 6 months, particularly if they rapidly cut down breastfeeding with the introduction of solids, and are encouraging their baby not to feed at night. Although this may be a cultural "norm" however, it is not physiologically normal for babies to have a rapid transition in their calorie intake in this way. Naturally babies are designed to begin to take in solids as a complement to breastfeeding at 6 months. This doesn't mean that breastfeeding reduces, but rather that solids are taken in addition to breastmilk. Mums who choose to use baby led weaning usually do see a more gradual shift from breastmilk to solids. It's important to note however that at 12 months breastmilk should ideally still make up most of a baby's calories, and often does with Baby Led Weaning and responsive breastfeeding on cue. A guideline based on the WHO recommendations for complementary foods would suggest that at 12 months between 70-75% of calories should come from breastmilk and the rest from solid foods. The guideline at 24 months is that a baby should receive 550 kcal from solids (total calorie needs is approx 1000-1400 kcal). Assuming a gradual transition throughout the 2nd year, at 18 months there may be 50-75% or more from solid foods, and at 2 years ideally 80% would come from solid foods. This might seem like a lot of calories from breastmilk, but at 24 months many babies are still feeding morning and bedtime and for nap, and could easily be drinking a few ounces at each breastfeed. If that seems strange, remember that a toddler is often recommended to have several portions of dairy a day - often amounting to 10 or 12 oz. That dairy is only there as a substitute for breastmilk.

The way in which solids are introduced can therefore play a big role in when fertility returns.

A WHO Multinational Study published in 1990 looked at the length of time for menstruation to return during breastfeeding. The study involved 4118 mothers and their babies across 7 countries. Two of the factors that were significant in determining when a women began menstruating were:

- Total amount of time at the breast over 24 hours. This isn't surprising given what we have discussed above as it is about the total time of suckling, and as a baby gets older he/she naturally reduces suckling time at the breast

- Balance of calories between breastmilk and other foods/liquids - the chance of menstruation returning increased substantially once the baby was taking less than 50% of calories from breastmilk. The time that a baby is taking 50% of calories from breastmilk can vary widely. A baby who is combination fed could reach this level within a very short time after birth, whereas a baby who is exclusively breastfed to 6 months (with no dummies etc) with a gradual introduction of solids through Baby Led Weaning, may not reach that level until somewhere between 12-18 months.

In Ecological Breastfeeding & Child Spacing, Kippley finds that women who breastfeed in this way have an average of 14.6 months post partum before menstruation occurs, with 8% getting their period back after 2 years.

It is normal and natural to have a significant length of time without having a period after giving birth. Of course other women follow a different pattern entirely, and while exclusively breastfeeding find they get their period back at just 3 months post partum. Kippley finds that 7% of women have a period in the first 6 months. Of course we know that although they are menstruating this doesn't mean that the women are necessarily fertile at this time.

The shift back to full fertility varies widely and indeed some women may not experience full fertility until they entirely wean their baby. It's a complex picture and interplay of many factors.

In Part 2 I'll cover breastfeeding as a method of birth control (lactation amenorrhea method) and trying to conceive while breastfeeding.

Further Reading

McNeilly Alan S. (2001) Lactational control of reproduction. Reproduction, Fertility and Development 13, 583-590. http://www.publish.csiro.au/RD/RD01056

McNeilly AS (1993) Lactational Control of Amenorrhea, Endocrinology and Metabolism Clinics of North America [01 Mar 1993, 22(1):59-73] http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/8449188

McNeilly AS (2001) Progress in Brain Research [01 Jan 2001, 133:207 214] http://europepmc.org/abstract/MED/11589131

The World Health Organization multinational study of breast-feeding and lactational amenorrhea. II. Factors associated with the length of amenorrhea

Fertility and Sterility , Volume 70 , Issue 3 , 461 - 471 http://www.fertstert.org/article/S0015-0282(98)00191-5/fulltext

Facts For Feeding - http://www.ennonline.net/linkagesproject2010

WHO Guidelines on complementary Feeding http://www.who.int/nutrition/publications/guiding_principles_compfeeding_breastfed.pdf

http://www.lalecheleague.org/llleaderweb/lv/lvdec98jan99p128.html

Jackson RL (1988) - Ecological Breastfeeding & Child Spacing. Clin Pediatr (Phila). 1988 Aug;27(8):373-7. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/3042247

Important Information

All material on this website is provided for educational purposes only. Online information cannot replace an in-person consultation with a qualified, independent International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) or your health care provider. If you are concerned about your health, or that of your child, consult with your health care provider regarding the advisability of any opinions or recommendations with respect to your individual situation.