I am an IBCLC (International Board Certified Lactation Consultant) in private practice in Northern Ireland and a La Leche League Leader with La Leche League of Ireland

Breastfeeding, Fertility and SubFertility: Breastfeeding in Pregnancy - are there risks?

This is part 3 of a blog series on Breastfeeding, Fertility & Subfertilty. Part 1 looked at breastfeeding and the menstrual cycle. Part 2 looked at fertility and avoiding or getting pregnant while breastfeeding. This third part looks at breastfeeding while pregnant, whether it can pose any risk to the pregnancy, things to consider about breastfeeding and common experiences.

Breastfeeding while pregnant may be an odd concept to some that don't know that it's possible, but many women do feed while pregnant. Some will wean while pregnant, either through choice or their baby self-weaning, and others will continue to feed through pregnancy and then tandem feed afterwards (feeding both their baby and toddler). Some women who never intended to breastfeed in pregnancy will find themselves doing it as they don't want to wean their toddler. Other women who really wanted to breastfeed in pregnancy can find they have awful nursing aversion in pregnancy and wean as they just don't want to continue. Just like the fertility experiences we discussed in Part 1 and Part 2, experiences of feeding in pregnancy can vary widely.

What happens to milk supply?

Although I want to concentrate on fertility, and safety/risks of breastfeeding during pregnancy in this blog, I think it's useful to have a couple of paragraphs on milk supply. I find that many women who are trying to get pregnant while breastfeeding don't realise the impact it will likely have on their milk supply, and the potential need to supplement their baby, and it's something which is important to consider before hand.

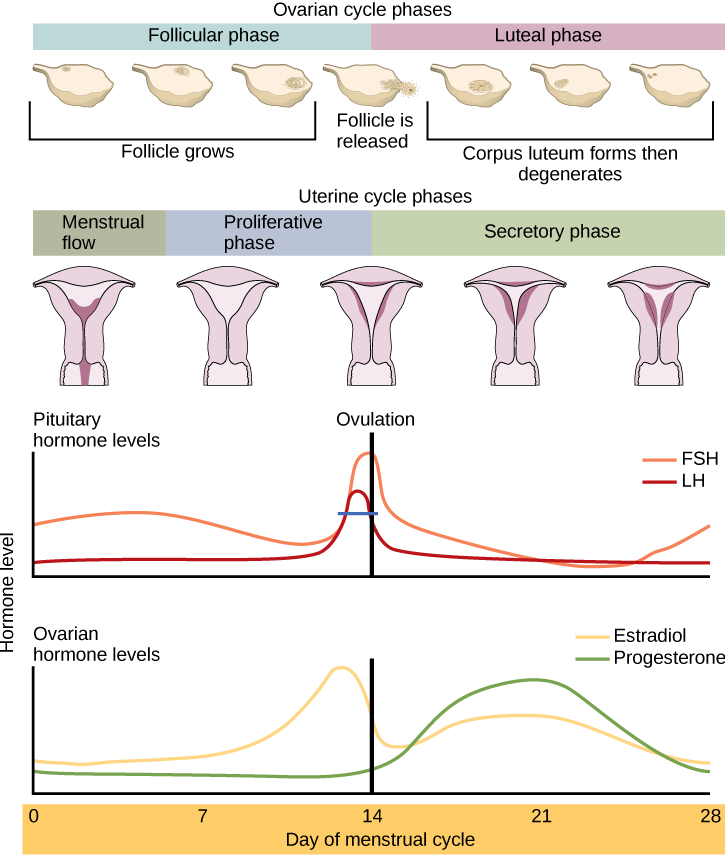

Once a pregnancy begins, progesterone levels begin to rise. This is due to the feedback loop which causes the corpus luteum to stay functional and producing progesterone rather than degrading (See Part 1). High progesterone has an impact on milk supply.

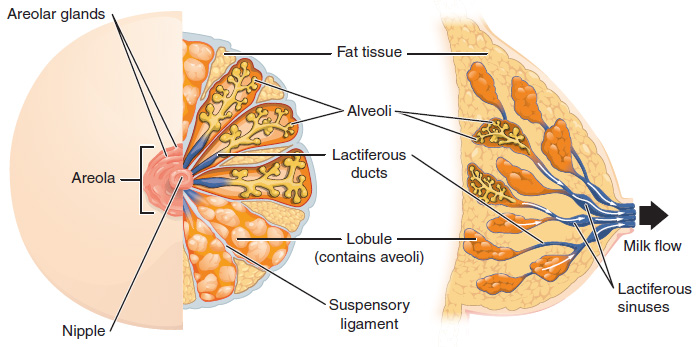

When we are breastfeeding, we store milk within alveoli, which are balloon type structures in the lobes of the breasts. Our breastmilk is made and then stored in these alveoli. Normally the walls of the alveoli are impermeable, and create a sealed container to hold the milk until the baby feeds. They are made impermeable due to tight junctions between the cells along the borders of the alveoli. When progesterone is high however (like in pregnancy) the junctions between the cell walls become leaky and so large quantities of milk can't be stored. The milk leaks out. This means that most women find that their milk volume changes in pregnancy, and becomes less. When it happens varies from woman to woman. Some notice a change in how often their baby/toddler is swapping sides and looking for more milk even as early as 6- 8 weeks. Most will certainly see a difference by the 2nd trimester. Along with this decrease in milk volume can be a change in taste. Milk may taste saltier. Some babies/toddlers don't mind this, and some object. Some toddlers even nurse, and then ask for a drink of water and then go back to nursing. Younger, not verbal, babies obviously are unable to tell you about the taste and if they feel a need for more hydration, but may be more fussy.

Although a very small number of women see no real change in milk volume, usually by mid pregnancy milk volume is very low as it changes to colostrum. In Adventures in Tandem Feeding, Hillary Flowers suggests that around 50% of nurslings wean during this time, and about 50% continue. How this drop in milk volume might affect your baby/toddler can be different depending on age. If your baby is much under 12 months and still dependent on milk as the main source of calories, you will likely need to add in a supplemental milk. If your baby is around 12 months increasing solids may be enough.

After birth the opposite process happens with the tight junctions. The delivery of the placenta causes a sudden drop in progesterone, and the junctions become tight and make the alveoli walls impermeable again. This allow large amounts of milk to be stored and the sensation of "milk coming in".

Having said that, let's move on to the safety / risks of breastfeeding during pregnancy. Many women are advised by healthcare providers to wean during pregnancy - but is this evidence based? What do we know so far....

Does Breastfeeding Cause an Increased Risk of Miscarriage?

Most of the resources I have read online on breastfeeding and miscarriage refer to the book Adventures in Tandem Feeding by Hillary Flowers. In her book Hillary deals with the potential risk of uterine contractions caused by breastfeeding and whether those may cause miscarriage. Hillary dismisses this as an issue because the receptors on the uterus to begin labour are not in place until shortly before birth. In my experience, women who are sensitive to the contractions can often feel them happening while feeding even early in pregnancy. This is often compared to the contractions of an orgasm, which in most women is not thought to be a risk to the pregnancy. In cases of high risk pregnancy however, some women are advised to avoid sex due to this risk. Hillary Flowers has summarised the information about contractions and the uterus in an article on the Kellymom site, which I have linked in the further reading section, and so I won't repeat the same information here. What I want to look at instead are the hormonal implications of breastfeeding in pregnancy, which I have never seen addressed well before.

If you haven't read Part 1 of this blog on fertility and subfertilty, then it might be a good idea to look at it first, or to refresh yourself with it if it's been a while. In Part 1 I talked about the gradual process of returning fertility while breastfeeding, and how for a significant period of time women may be subfertile. In a subfertile state the woman may be having regular cycles, and be ovulating in each cycle, but hormone levels may not be where they would be if she were not breastfeeding.

I also wrote about the research on how suckling interferes with the GnRH pathway and increases the suppressing effect of oestradiol. McNeilly's 1993 article "Lactation Amenorrhea" stated:

Suckling appears to suppress the normal pattern of pulsatile release of GnRH

and hence LH and prevents the normal growth of follicles.

The normal positive feedback effect of estrogen on LH release is abolished,

and estradiol exerts an enhanced negative feedback effect on both LH and FSH.

Thus, while suckling continues, any follicle that starts to develop and secrete estradiol will inhibit further LH release and therefore stop growing.

When suckling declines, the pulsatile pattern of LH returns to normal,

sensitivity to estrogen negative feedback declines, and follicle growth can continue and ovulation will occur.

So suckling prevents the normal growth and maturation of follicles. We also know that from Part 2, McNeilly stated that

After the return of menstruation during lactation, the frequency of ovular cycles progressively increases but does not return to normal until complete weaning has taken place.

Many women find that when breastfeeding, their luteal phase is short. We know that the luteal phase lasts as long as the corpus luteum lasts. After ovulation, the corpus luteum produces high levels of progesterone. The corpus luteum should continue to function for around 12 days and then begin to degrade. As the levels of progesterone drop, the uterine lining is shed, around 14 days after ovulation. If the luteal phase is shorter than this, it is due to the corpus luteum degrading earlier than it should. It ran out juice, or had produced as much as it could essentially. This may be due to lower hormones at the start of the cycle. Lower oestradiol due to breastfeeding may result in a slightly less mature egg, and therefore a slightly less mature corpus luteum that just doesn't last as long.

This is significant in pregnancy because the corpus luteum function is vital in early pregnancy. When pregnancy begins, a feedback mechanism stops the corpus luteum from degrading and causes it to continue functioning and producing high levels of progesterone. The corpus luteum continues this function until the placenta fully takes over, which begins around 8 weeks, but doesn't complete until 14 weeks. So the corpus luteum needs to be functioning right until the end of the first trimester. Is it possible that a woman with a short luteal phase who gets pregnant could have a corpus luteum which runs out of energy and function before 14 weeks?

A 2008 study by Arck et al in Reproductive BioMedicine Online found that the risk of miscarriage was significantly increased in women who had lower progesterone prior to the onset of the miscarriage, and recommended progesterone supplementation to support the pregnancy and decrease the risk. A Cochrane Database Systematic Review done in 2011 by Wahabi et al found that inadequate progesterone in early pregnancy is linked to miscarriage and that supplementing with progesterone is an effective in preventing early miscarriage. Many fertility clinics do supplement women for the first trimester (sometimes up to 20 weeks) with progesterone in order to maintain the pregnancy. Progesterone supplementation in pregnancy has also been found in a Cochrane review to reduce the risk of pre-term birth in women with previous preterm birth and in women with a short cervix.

Tracking your cycle (See Part 2) will allow you to get a sense of what your hormonal profile is like before you conceive, and whether you are having a normal luteal phase, or whether your progesterone levels may be a little low. A progesterone test with your GP is another way of checking your progesterone levels. This is often referred to as a Day-21 progesterone test. This "Day-21" figure comes from the idea that ovulation happens on day 14. If you do not ovulate on day 14 (and many don't), then the test should be done 7 days after ovulation, not on day 21. The NHS considers a progesterone level of over 30 nmol/L to be normal and to demonstrate that ovulation has happened. Some fertilty clinics however see 30 nmol/L as a subertile figure and an indication that a slightly immature egg has ovulated, and would consider a level of 60 nmol/L to be optimal.

Obviously many women breastfeed through pregnancy and have entirely normal and healthy pregnancies and births, including women who have a short luteal period. There are also very many women who have miscarriages when they are not breastfeeding. Miscarriage occurs in around 1 in 4 pregnancies, so is already a pretty high risk, regardless of breastfeeding. Although there is usually no way to know why a miscarriage has occurred we do know that there are risk factors.

Age is a risk factor (20% of pregnancies in women aged 30-39 end in miscarriage compared to 10% in women under 30). Smoking, alcohol, excess caffeine, thyroid conditions, low body mass index are all risks. Low progesterone is also a risk factor, and a short luteal phase (which may be due to breastfeeding) can be a symptom of low progesterone. Could this mean that in some women breastfeeding was a risk to the pregnancy before conception began? Does continued suckling during the early pregnancy for these women have a further effect to hormones? There is very little data on any of this, and every woman needs to make the decision on whether you feel breastfeeding poses any extra risk for you or not. If you are an older mother, have a luteal phase of 10 days when breastfeeding, and have been finding it difficult to conceive while breastfeeding, you may come to a very different conclusion about the risk than a younger mother who is breastfeeding, has a 14 day luteal period and got pregnant very quickly and easily while breastfeeding. There is no right or wrong decision as to whether you should breastfeed in pregnancy or whether you should wean. Neither route is better than the other, and each woman has to weigh up what will be the best overall route for her within her family circumstances.

Breastfeeding Aversion

Although some people breastfeed in pregnancy with no discomfort at all, most probably do have stages where they aren't enjoying it so much. Nipple pain is common in pregnancy due to the hormonal changes, and many have periods of breastfeeding aversion, where they find breastfeeding unpleasant, or in some cases feel strongly that they just want the nursling to stop right now. Adventures in Tandem Nursing (linked below) is a great resource for this which talks through different mother's experiences, how long it lasted and how they managed those feelings. It can be very helpful to know that those feelings are common. What is interesting to me about breastfeeding aversion is that it tends to occur at times of pregnancy, ovulation or menstruation. They are important times for the reproductive cycle. Women often respond by feeding less, or for shorter periods as a coping mechanism. Is it possible that the body is giving us signals at that time to reduce sucking stimulus, in order to optimise our hormone secretion and create the maximum chance for a further healthy pregnancy?

Any other considerations in pregnancy

Other than miscarriage, is there anything else to consider when breastfeeding in pregnancy? This is what we know from the research. A number of studies have looked at whether breastfeeding affects the weight of the baby at birth, and found that there was no significant difference between expected weight and birthweight. One study of Guatemalan women however found that although the difference was not significant, newborns tended to be lower in birthweight the longer the older child fed into the pregnancy (Merchant et al 1990). They also found that the mothers who breastfed had reduced maternal fat stores despite consuming more of the nutritional supplements than other mothers. The authors concluded that the fetus was protected at the expense of the mother, so being aware of your own diet being adequate may be important. This isn't really surprising given the demands on the mother's body when both gestating and lactating.

A Peruvian study (Marquis et al 2002) looking at 133 women who breastfed in the 3rd trimester found that the babies had lower weight gain during the first month of life. The babies spent more time breastfeeding, but took in less milk. In one third of the cases the older sibling was being breastfed after birth, so it might be fair to think that perhaps the baby was gaining less weight due to the older sibling feeding, but the authors discounted this as a cause of the low weight gain. In fact babies where the older child was weaned in the 3rd trimester took in least milk, those who were tandem feeding took in more, but the babies where there was no breastfeeding in pregnancy took in most milk in that first month, and gained weight best. In this study BFP refers to Breastfed in Pregnancy. NBFP refers to Never Breastfed in Pregnancy.

When milk intake of the other child was considered as part of total milk production, the difference between BFP and NBFP mothers was reduced. The mean 1-month intakes of infants increased progressively from BFP/no tandem breastfeeding (762.5 ± 232.4 g/24 hour), BFP/tandem breastfeeding (768.6 ± 192.3 g/24 hour), to NBFP (813.0 ± 161.8 g/24 hour), demonstrating that tandem feeding did not account for the low milk intakes of BFP infants.

Whether this is applicable to Western societies with different diets is not clear.

So - is breastfeeding a risk to pregnancy? Short answer - maybe, maybe not. It really depends on the individual circumstances - the family trying to conceive, their fertility/subfertility status, their obstetric history, and how much breastfeeding is impacting that individual woman. It also depends on what you define as risk - is miscarriage, pre-term birth etc the definition for you, or is an effect to weight gain, or larger draw on your own nutritional stores a risk for you? Some women have had several pregnancies while breastfeeding subsequent children, and others very clearly feel that breastfeeding may have impacted their miscarriages, pre-term births or their ability to conceive. Tracking your cycle when it returns can give you an insight into how breastfeeding is affecting you, as well as helping you to understand your own bodily processes in a much clearer way.

Fertility while breastfeeding is something I feel really passionate about - helping women to understand how it affects them and their cycle and hormones. That passion comes from a personal journey and some difficult personal experiences. For those of you who find that trying to conceive while breastfeeding is much more difficult than conceiving when you are not breastfeeding - I understand the difficult emotions involved with that. It's important to remember just how much you are asking your body to do, and how much your body is already doing. The lactating breast uses more energy than your brain! You are creating a superfood, building an immune system, creating a personalised medicine. The Lancet Breastfeeding Series states:

If breastfeeding did not already exist, someone who invented it today would deserve a dual Nobel Prize in medicine and economics. For while “breast is best” for lifelong health, it is also excellent economics. Breastfeeding is a child's first inoculation against death, disease, and poverty, but also their most enduring investment in physical, cognitive, and social capacity.

Looking at it from an industrial perspective, Jon Eliot Rhode writes on economics:

The lactating mother is an exceptional national resource, for not only does she process coarse cheap foods to produce a unique and valuable infant food, but also the production process (lactation) provides immeasurable benefits to health.

Pregnancy and breastfeeding are both everyday miracles and we forget just how amazing they are and what an amazing job your body is already doing. Look at your nursling, and remember!

If you have any questions about a consultation or would like to arrange to meet, please get in touch.

Further Reading

Hillary Flowers on uterine contractions and breastfeeding in pregnancy - http://kellymom.com/pregnancy/bf-preg/bfpregnancy_safety/

References:

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1023%2FA%3A1018707309361?LI=true

http://kellymom.com/pregnancy/bf-preg/bfpregnancy_safety/#contractions

http://europepmc.org/abstract/med/8449188

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Corpus_luteum

http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1472648310603008

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/22161393

https://www.naprotechnology.com/infertility.htm

http://www.nhs.uk/Conditions/Miscarriage/Pages/Causes.aspx

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2403056

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2375294

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2782541

http://journals.lww.com/greenjournal/Abstract/2008/07000/Progesterone_for_the_Prevention_of_Preterm_Birth_.22.aspx

https://www.researchgate.net/publication/24080949_Mothers'_Milk_and_Measures_of_Economic_Output

http://www.thelancet.com/journals/lancet/article/PIIS0140-6736(16)00012-X/abstract

Important Information

All material on this website is provided for educational purposes only. Online information cannot replace an in-person consultation with a qualified, independent International Board Certified Lactation Consultant (IBCLC) or your health care provider. If you are concerned about your health, or that of your child, consult with your health care provider regarding the advisability of any opinions or recommendations with respect to your individual situation.